By Delman Lebel, head of U.S. Corporate Affairs at Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease and Chair of the Rare Disease Company Coalition

Finding cures for rare diseases is a fundamentally nonpartisan pursuit. That’s why members of the Rare Disease Company Coalition (RDCC) are calling on our elected leaders to seize this unique opportunity for bipartisanship, reach across the aisle and unite on common-sense legislation to offer hope to millions of Americans living with rare diseases.

Right now, over 30 million Americans, many of whom are children, live with a rare disease. These aren’t abstract medical conditions; they’re the daily realities for families facing diagnoses that too often carry a devastating prognosis – and a glaring lack of treatment options.

A staggering 95% of these 10,000 diseases lack FDA-approved therapies. Diagnosis can take years, and during that time the disease can quickly progress. For those in need of treatment the clock is ticking, and the key to progress lies with our lawmakers.

As Chair of the RDCC, an advocacy-focused coalition representing life science companies committed to discovering, developing, and delivering rare disease treatments for patients, I understand the unique challenges that come with advancing rare disease therapies. Developing treatments for rare diseases involves creating animal models from scratch, difficulty in recruiting participants for clinical trials, and navigating high costs and risks. It often takes over a decade of sustained investment to move from bench to bedside. Because each disease affects a small population, traditional market incentives are insufficient. This is why a robust and supportive ecosystem with key incentives is crucial. To foster this kind of ecosystem, we need the support of Congress.

Three bipartisan, common-sense legislative priorities offer a concrete path forward to ensure scientific breakthroughs continue and the roughly 30 million Americans living with a rare disease are not left behind.

First, we need to remove barriers that hinder scientific progress, such as the disincentive within the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that hinders rare disease innovation. The IRA’s Orphan Drug Exclusion provides a price negotiation exemption for orphan drugs that treat only one orphan, or rare, condition. However, 1 in 5 orphan drugs are FDA-approved for more than one use, and 60% of those second indications are for another rare disease. This unnecessary hurdle discourages companies from further pursuing promising research that could lead to additional treatment options. The ORPHAN Cures Act would expand the single-orphan exclusion, allowing companies to follow the science and invest in promising treatments using existing research. This means more treatment possibilities would be within reach.

Second, we must preserve incentives to develop therapies for rare diseases. The rare pediatric disease priority review voucher (PRV) program has been a proven success, encouraging drug development for rare pediatric diseases by expediting the regulatory process for qualifying products. Since its inception, the PRV program has led to the approval of dozens of life-changing therapies for children, benefiting over 200,000 patients and addressing high unmet needs across 47 rare pediatric indications. However, as of December 20, 2024, the PRV Program has lapsed and begun to expire. Without urgent Congressional action, this incentive, along with hope for millions of children, may vanish for good.

Finally, we must restore the Orphan Drug Tax Credit (ODTC) to its original value. This credit is essential for many small biotech companies leading rare disease research. It promotes research by lowering development costs for manufacturers, reducing the significant financial cost and risk that comes with creating new therapies for small patient populations.

The ODTC was cut in half in 2017 and we are already seeing a chilling effect, making it harder for these companies to pursue potentially life-saving research. Rare disease companies saw nearly $10 billion less in investment available for research in 2022, stemming from decreases in venture capital investments, the IPO market, and partnership revenues. Restoring the credit isn’t just smart policy; it’s a moral imperative. Without it, many promising projects will simply never get off the ground, leaving patients with little hope for treatment.

These aren’t just legislative checkboxes; they are essential to preserve the delicate ecosystem of rare disease research and development, ensuring that scientific progress can continue despite the challenges. They create hope for families who have spent far too long searching for answers.

Policymakers have a chance to make a real difference, to show the American people that bipartisanship isn’t dead and that progress is still possible. By prioritizing these common-sense measures, our lawmakers can send a powerful message: the rare disease community matters, their struggles are seen, and healthier futures for patients living with a rare disease are worth fighting for.

By Curt Oltmans, Chief Legal Officer of Fulcrum Therapeutics and Chair of the Rare Disease Company Coalition

For people living with a rare disease, many feel as though they have to face their journey alone. With over 10,000 distinct disease states — 95 percent of which have no cure — the path from diagnosis to care can be complicated, frustrating and costly.

But rare disease is not rare. Over 30 million Americans live with a rare disease, the same number of people in the U.S. living with diabetes. But patients living with a rare disease are often under-researched, underserved and misunderstood, and it doesn’t have to be that way.

Last week was Rare Disease Week, an annual occasion to come together with a hopeful vision for the future of rare disease research and patient care. It is an occasion we use to remind ourselves, and our lawmakers, that there is no time to lose in our mission to discover, develop and deliver treatments to patients living with a rare disease. Half of all rare disease patients are children, and a third of those children won’t live to see their fifth birthday.

Rare disease drug developers must continue to pursue scientific innovation and breakthroughs, but unfortunately, policymakers are currently on a dangerous path of creating obstacles to innovation, threatening the existence of rare disease companies.

As Chair of the Rare Disease Company Coalition (RDCC) and Chief Legal Officer at Fulcrum Therapeutic, I’ve spent years meeting with patients whose stories break my heart, and whose strength fuels our mission to improve the lives of patients with genetically defined rare diseases.

At Fulcrum, one of our key areas of focus is around Sickle Cell Disease – a condition that primarily affects African-Americans. In a community that is already subject to widespread healthcare inequity and mistreatment within the broader healthcare system, those who suffer from Sickle Cell Disease are faced with a painful, life-shortening disease with few treatment options.

We’re able to invest in this kind of research in large part due to the passage of the Orphan Drug Act in 1983, which created a set of incentives for researching rare disease treatments in addition to treatments for common diseases and conditions. Over the past 40 years, the number of orphan drugs skyrocketed by 1,576% – from just 38 to more than 600 treatments for more than 1,000 rare diseases.

While the scientific landscape has transformed over the last 40 years, opening up a wide range of new possibilities for our work, the legal and regulatory environment has not kept up.

Right now, there are several avenues that federal lawmakers and regulators can take to shape and improve the next decade of this work for the better. For instance, the ORPHAN Cures Act would encourage rare diseases research and development by expanding the IRA’s Orphan Drug Exclusion to include multiple rare disease indications. This change allows rare disease companies to follow the science and explore promising research that could lead to additional treatment options. For RDCC members, who spend on average half their annual revenue on R&D, this is a critical fix.

Additionally, it is critical that Congress reauthorize the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher (PRV) program. The program provides a crucial incentive to direct research and resources toward drug development for our most vulnerable population – our children. Over the past decade, the PRV program has proven itself to be a critical incentive for decision-makers in the rare disease space – from CEOs to venture capitalists – to pursue research in pediatric populations. And it comes at no cost to taxpayers. By reauthorizing the program, Congress can help rare disease drug developers help children living with a rare disease.

Improving, or even saving, the lives of people living with a rare disease is a nonpartisan issue. On the heels of a powerful Rare Disease Week, we are reminded that while these conditions may be “rare,” the community we serve is large. And while research and treatment challenges we face may be enormous, the need for solutions is even bigger.

At Fulcrum and among all rare disease innovators in the RDCC, we remain committed to the rare disease community, and strongly advocate for smart policy to ensure we can continue doing the work we love. I have never been more optimistic about the opportunities we have in the current scientific landscape. Now, we just need support to meet the moment – and it’s up to Congress to rise to the occasion.

By Mike Hu, cofounder of Project GUARDIAN

The benefits of early diagnosis and treatment have been well documented, with plenty of examples in cardiovascular diseases, infectious diseases, and cancer. In rare genetic diseases, early diagnosis is arguably even more critical and can bring night and day differences in outcomes, just like what my kids have shown me.

In 2011, my sons were both diagnosed with Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II (MPS II). A single nucleotide change caused a key lysosomal enzyme to be non-functional. As a result, large sugar molecules called glycosaminoglycans (GAG) accumulate in all their bodily tissues, leading to joint contractures, organ malfunction, developmental delay, and eventually premature death. Following the same enzyme replacement treatment from the age of 4 and 1, their outcomes have been very different. While my older son has very stiff joints causing difficulties even for walking, his younger brother can swim and ride a bicycle. The younger one can also put together 300-piece puzzles while the older one can’t even finish a 12-piece.

Unfortunately, early diagnosis is far from the norm in rare genetic diseases. Diagnoses are typically prompted by emerging symptoms, and often take a long time due to the rarity of such diseases (AKA the “Diagnostic Odyssey”). As the symptoms are generally signs of accumulated irreparable damage, treatment attempts at correcting the root cause are doomed to have poor efficacy: how can we expect the necrotic joints and dead neurons to be revived by the replacement enzyme that could only slow down the GAG accumulation at best? The same treatment was much more effective for my younger son who benefited from his older brother’s diagnosis and started treatment when he was pre-symptomatic, when the damage was still minimal. This, in turn, becomes a critical challenge to therapeutic development. While it’s easy to recognize the importance of enrolling patients at a time when the treatment is most efficacious, the reality is that virtually all patients are only identifiable after symptom presentation, giving the clinical trials bleak prospects from the get-go.

How can we diagnose early before symptoms emerge? How can we treat early or enroll patients when the drug candidate has the best chance to be effective? The answer lies in newborn screening (NBS). From phenylketonuria (PKU) to spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), the transformative power of early identification and effective treatment for dozens of rare genetic diseases has been demonstrated by the millions of babies whose lives have been saved. In the US, NBS is a national public health program with state infrastructure to screen for up to 63 diseases on the Recommended Universal Screening Panel (RUSP). A nomination system is in place to add conditions to the RUSP when there is sufficient evidence that newborn screening for the condition meets technical standards, is accepted by parents, and has available effective treatment. This approach is not without its own challenges, of course. The process to get a single condition through from nomination to decision takes 4-6 years on average. In the past 15 years, only 8 conditions were added to the RUSP. The lack of neonatal natural history, prospective screening data and effective treatments, and the high costs of screening are all nearly insurmountable for individual disease nominations.

GUARDIAN (Genomic Uniform-screening Against Rare Diseases In All Newborns) aims to change this. Our goal is to enable the screening of newborns using genome sequencing to identify pre-symptomatic babies and support early intervention by either using existing treatments or enrolling in clinical trials of novel treatments, all at a disease stage when treatment could be maximally efficacious. Sequencing based genomic NBS can significantly expand NBS to rare genetic diseases with a single common platform and provide synergies across conditions to decrease the cost per condition for screening and de-risk the strategy across diseases/companies supporting the platform. Investment in pilot studies of genomic NBS will support clinical trials to develop new treatments and will identify infants who are candidates for treatment once those medications/treatments are FDA approved. GUARDIAN is led by Dr. Wendy Chung who previously led the SMA NBS pilot study that serves as a prime example of a public-private collaboration, which successfully transformed a once deadly disease from no treatment and rejected by the RUSP to having multiple effective treatments and successfully being added to the RUSP. Most importantly, SMA babies undergoing timely treatment have been growing, meeting milestones, and enjoying their lives like other children. Under Dr. Chung’s leadership, GUARDIAN was launched in 2022 in New York state. With over 5000 babies already enrolled, the study is a multi-year pilot research program aimed to enroll a minimum of 100,000 newborns and screen them with a starting panel of ~250 diseases (and growing). Families with newborns who screen positive are offered information about all treatment options and clinical trials available to facilitate early treatment. Natural history and long term follow up and outcome data are being collected for all babies who screen positive. The results will be used to demonstrate the benefits of NBS for these conditions to support a RUSP nomination for routine screening.

The GUARDIAN team believes that all babies affected by severe genetic diseases deserve what the SMA babies have benefited from. We need your support! Contact us today to discuss how you can help, and together, let’s make sure all beloved babies have a healthy start.

By Giacomo Chiesi, Head of Chiesi Global Rare Diseases

As a certified Benefit Corporation (B Corp) serving the needs of rare disease patients, we believe we have a societal obligation to address policies impacting the estimated 350 million people living with a rare disease. The unmet need is overwhelming, as less than 5-10% of known rare diseases have a treatment. A recent call from leaders in the United States Congress to ban the use of the Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) metric in all federal programs could go a long way toward correcting profound societal inequities impacting rare disease patients and caregivers – and may provide a financial benefit as well.

QALY-based assessments imply that the value of an intervention is proportional to the beneficiary’s capacity to benefit, which therefore favors those with “more treatable” conditions and those with greater potential for health, in terms of functioning and/or longevity. We, alongside our colleagues at the Rare Disease Company Coalition, argue that while QALY can be a useful part of assessing the economic value of healthcare treatments and outcomes for high prevalence diseases, use of QALY for orphan drugs is a prime example of how blunt use of traditional health policy can discriminate against rare disease patients.

The traditional QALY measure focuses on gain in lifespan but does not reflect health gains reported by patients with rare diseases that have few if any treatment options available; nor does it incorporate what patients value in a treatment such as less frequent dosing or reduction in infusion schedules. Fortunately, the use of QALY to assess the value of cell and gene therapy for the treatment of rare diseases has been, in few cases, positive as it drives HTAs/payors to arrange value-base or managed access agreements to manage the high upfront cost of these therapies, enabling access.

As health care costs often begin in childhood for about half of all rare diseases, this can perpetuate a misconception among payers that rare disease treatments are too costly. This misconception further discriminates against a vulnerable population and overlooks that the cost of therapeutics for rare diseases is small compared to the average annual economic burden shouldered by patients and their families.

That misconception exists because some issues disproportionately impact the rare disease community, including process of care, indirect costs such as productivity loss, long term or short term disabilities, home changes, and traveling and accommodations for medical visits.

In 2020, Chiesi Global Rare Diseases commissioned a health economics study to measure the societal value of pharmaceutical treatments for rare diseases and inform policymakers about the unmet needs of the rare disease community in the United States. We estimated that the overall burden of rare diseases in the U.S. is $7.2 trillion to $8.6 trillion per year. That is approximately ten times higher than high-prevalence diseases on a per patient per year (PPPY) basis. A lack of treatment for a rare disease was associated with a 21.2 percent increase in total costs.

While most rare disease direct costs are covered by insurers, we found that an important part of indirect costs remain on the shoulders of patients and families. People living with a rare disease often depend on a family caregiver, which impacts that individual’s health, quality of life and economic stability as well. When no treatments were available, our study showed that the range for productivity loss per year was approximately $33,000 to $61,000 for patients and $25,000 to $61,000 for caregivers, compared with approximately $3,000 to $22,000 for patients and $4,000 to $5,000 for caregivers when treatments were available.

These findings highlight that providing access to rare disease treatments generates substantial value for society because it potentially lowers the associated economic burden on patients and caregivers. But assessments like QALY do not consider the indirect costs or non-health-related benefits such as the ability for caregivers to work and improved productivity at work. Also omitted in QALY assessments are patient and caregiver reported outcomes, such as value of hope and value of knowing. Both can provide quantitative and relevant information regarding the impact on daily life.

Declaring access to rare disease therapies a public health priority will likely lead to further investment in treatments. A public health priority designation can lead to restored incentives and further rare disease drug development and would support ongoing Congressional calls for a coordinated approach at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to provide regulatory reliability and expertise in its rare disease product reviews.

Public policy should increase caregiver resources and provide relief for families affected by rare diseases, as they bear high indirect or non-reimbursed expenses. Congress can and should do more by investing in the care economy, recognizing that rare disease family caregivers are an important segment of the infrastructure equation. We often hear mixed messages from government regarding access, drug pricing and innovation that risk perpetuating existing health disparities. We need to recognize that working together for the unified purpose of delivering treatments for rare disease patients is a societal imperative. The dignity and insight of the rare disease patient and caregiver should inform our progress.

Learn more about improving patient access to life-changing, FDA-approved rare disease therapies in this new Rare Disease Congressional Coalition policy paper.

By: Sheila Frame, President, Americas at Amryt Pharma and serves as a Board Member of the Rare Disease Company Coalition. She has spent more than 20 years in the biopharmaceutical industry, including in commercial leadership roles at Novartis and Bristol Myers Squibb.

Originally Published at RealClearScience.com (January 18, 2023)

The United States Congress is officially a house divided with the two chambers controlled by rival parties. The split will significantly affect either party’s ability to pass significant legislation through Congress, possibly resulting in two years of partisan deadlock that may remain unresolved until the next election cycle in 2024. Political polarization has become our new normal. Yet, I believe there are some areas where Americans can and do stand united. One of those areas: supporting health care for our kids.

In the US today, approximately 30 million people live with a rare disease, about half of whom are children. While many of these diseases are inherited at birth, they are also chronic, can worsen over time, and are often life-threatening. As the 118th Congress begins in January and works to identify areas of bipartisan compromise – accelerating diagnosis, advancing cures and supporting access to patient care for these 15 million kids can be a bipartisan victory.

It is important to recognize achievements from the 117th Congress that will disproportionately benefit kids with rare disease. In particular, the reauthorization of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act included the establishment of a Rare Disease Endpoint Advancement (RDEA) Pilot Program. This new program seeks to advance rare disease drug development programs by providing new ways for clinical trial sponsors to collaborate with the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). This will support identification of new endpoints to measure a medicine’s effectiveness, hopefully leading to more effective rare disease therapies while reaching patients sooner. This program is a noteworthy example of the progress that can be accomplished when policymakers and the innovative biopharmaceutical community collaborate with patients’ best interests in mind. Yet, with over 90% of rare diseases without an FDA-treatment, there is so much work left to do.

Continue reading at RealClearScience.com.

By Dr. Brian Roberts, Chief Medical Officer, Rezolute Bio, a member company of the Rare Disease Company Coalition

We are in a pivotal era of rare disease innovation that originated 40 years ago with the passage of the Orphan Drug Act (ODA). As a practicing endocrinologist, researcher and drug developer with considerable experience in the rare disease area, it is humbling for me to witness the many research institutes, biotech companies, policy organizations and patient advocacy groups that are unwavering in their commitment to those impacted by rare illnesses. I stand with them in their commitment to creating novel, life-changing treatments for rare and ultra-rare diseases and helping to increase access of these therapies to patients living with these conditions.

While impressive progress has been made in the last 40 years, over 10,000 rare diseases still impact an estimated 25-30 million Americans, and at least 95% of them still lack an FDA-approved therapy. More important than the numbers are the people these diseases impact daily. Rare diseases inflict a tremendous burden on patients, their families and caregivers, often making the simplest daily tasks incredibly challenging. Thanks to the ODA and organizations like the Rare Disease Company Coalition (RDCC) that advocate for changes in health policy and incentives for significant scientific advancements, important discoveries continue to be made that positively impact patients and bring new therapies for rare disease.

A disease like congenital hyperinsulinism (HI), a serious, rare pediatric disease, affecting 1:25,000 – 50,000 children born in the U.S., is just one example of a rare disease with a high unmet need for new therapies. HI presents most commonly in the first month of life, causing dangerously low blood glucose and placing developing brains at significant risk for irreversible damage. There are no regulatory-approved medical therapies for all forms of HI. Currently available therapies are repurposed drugs that were not developed for HI or a pediatric population, have serious side effects, and are inadequate in controlling hypoglycemia for a majority of HI patients. When currently available medical therapies fail, families must choose between intensive medical/feeding regimens or a near-total pancreatectomy. New potential therapies for rare conditions like HI are now in development and are the direct result of the ODA. More policies and regulations that encourage research and development of treatments for the rare disease community are still very much needed.

Working in the rare disease space and being able to develop meaningful drug therapies is incredibly gratifying. My colleagues and I are motivated by the possibility of helping improve the lives of very specific groups of patients by providing better therapies to patients and families, who have suboptimal treatment options. That’s a great feeling. The orphan drug and rare disease revolution may have its origins in the ODA, but it’s driven by the passion and innovative thinking of physicians, scientists and the broader biotech community who are pioneering breakthrough innovations in small, entrepreneurial companies. At Rezolute, we are one such company, committed to developing bold medicines that transform the lives of patients. We are advancing RZ358 as a novel therapy for those living with HI thanks to the dedication of our team members, the close partnerships we have formed within the rare disease community and organizations such as RDCC.

While the ODA was the original impetus in launching the meteoric rise of orphan drug development, a renewed sense of urgency is now underway. Rare disease biotech companies need continued substantial incentives to support continued research and development of orphan drugs for conditions like HI, and so many more that affect millions globally. Like many biotech companies, our ability to bring forward new therapeutics is mainly dependent on successful clinical trials. While Rezolute was able to successfully complete our recent pediatric rare disease trial, in spite of challenging circumstances during the pandemic, many clinical trials were significantly impacted or even halted. Trials became even more challenging to complete, given the greater health concerns of rare disease patients and numerous logistical roadblocks. Actions to extend exclusivity for orphan drugs, whose development was disrupted during the pandemic, is just one way to incentivize companies to complete these trials and bring new treatments and cures to patients battling rare diseases.

I’m hopeful for the future of rare and orphan drug disease development and call on Congress for its full support of the ODA so the biotech community can continue working to transform the lives of patients and their families.

Learn more about the Orphan Drug Act and the RDCC’s commitment to furthering innovation for a community that long deserves life-changing treatments.

By: Amanda Malakoff, Executive Director, The Rare Disease Company Coalition

The state of the biotech industry is at a critical inflection point. From one perspective, people are calling this era the golden age for biotech, where cutting edge medical discoveries are showing incredible promise. For example, rare disease biotechs have recently pioneered the ability to treat patients by permanently modifying a single gene to cure disease. It’s thanks to recent medical and technological innovations like these that there has never been a more dynamic time for biotech. However, from another perspective, capital is fleeing the rare disease biotech industry, prompting concerning headlines like “Biotechs face cash crunch after stock market ‘bloodbath’.” This paradox makes it easy to see why, despite the incredible innovations being made in biotech today, it is becoming increasingly difficult to realize the full potential of promising biotech innovations.

The Rare Disease Company Coalition (RDCC) represents nearly two-dozen life sciences companies that are researching, developing, and bringing treatments to rare disease patients – often those who previously had no options available to them – thanks to breakthroughs in molecular, cell, and gene therapy. Last month, I represented the RDCC on a panel discussion on the State of the Industry at The Business of Rare Policy Summit in Washington, DC, where experts and stakeholders came together for a day of dialog.

My fellow panelists and I spoke to the challenges facing clinical stage rare disease biotechs today. Namely, without products on the market, they do not bring in revenue and are largely dependent on capital markets to fund their research. However, it’s not just clinical stage companies relying on investment for research and development (R&D). Due to the complex nature of rare diseases, a comparatively higher percentage of operating expenses is dedicated to research and development all rare disease life science companies. Commercial stage companies with treatments on the market continue to invest their profits back into R&D, spending more on research than they make in revenue. As a result, commercial-stage rare disease companies often must raise billions of dollars from investors to sustain R&D.

Unfortunately, the recent downturn in the biotech stock market is keeping promising treatments from coming to market and has left an industry once flooded with money now strapped for cash. During times of economic uncertainty, investors look for lower risk portfolios, and look to key inflection points and milestones in the pharmaceutical regulatory review process. By its nature, the rare disease drug development process incurs more risk. Treatments are manufactured for limited population sizes, but their development costs remain the same or higher than drugs for larger populations due to the lack of natural history, complex diagnosis, limited access to patients for participation in clinical trials, and the often-unprecedented regulatory pathway. Public policy has a huge impact on raising capital and getting treatments to market, yet the government’s lack of consistency in addressing these challenges is putting undue constraints on potential private investment.

Investors want certainty and often look to policies made in Washington as key indicators. A “one-size-fits-all” approach to policies like drug pricing and value assessment frameworks can be especially detrimental and destabilizing to rare drug development. Amidst the current economic headwinds, it is more important than ever for Congress to preserve and foster biotech innovation so that the gains that have been made are not lost. Supportive federal regulations and policies are sorely needed to help spawn private investment in the rare disease biotech industry.

Let’s look at hard numbers to illustrate this point. Policies like the Orphan Drug Act (ODA), which was enacted in 1983 to facilitate the development of treatments for rare and ultra-rare conditions, has had outstanding success in furthering the industry. Prior to the ODA, only 38 orphan drugs had been approved in the US, compared to over 700 today. However, in 2017, some in Congress halved the Orphan Drug Tax Credit to 25%, and significantly reduced this powerful incentive made possible under the ODA for companies to invest in cures for rare diseases. Given that less than 7% of all rare diseases have an FDA-approved treatment, we simply cannot afford to reduce incentives to find, treat and cure rare diseases.

Policies must account for the complexity of rare disease drug development, which requires substantially different – and often more costly – trial designs and business models than therapies for larger patient populations. To offset the higher risk and costs associated with rare disease research, Congress must do more to provide incentives and increased certainty for rare disease companies by strengthening policies like the Orphan Drug and R&D tax credits. Doing so would send a reassuring signal to investors and help companies secure critical funding needed to continue their important work.

Rare disease research is at a precipice where years of efforts and innovation are yielding incredible results with the potential to give patients a better chance at life. Researchers, doctors, and patients are working together to advance cutting edge medical innovation, presenting us with an extraordinary opportunity to bring hope to the more than 90% of rare disease patients that lack treatment today.

While the financial challenges facing the biotech industry are significant, the solutions are straightforward. Rare disease biotechs need investors, and investors look to decisions made in Washington to provide certainty. With so many promising therapies on the horizon, it is imperative that policymakers act now to ensure the continued success of the industry. We are on the precipice of a golden age for biotech, and to fully realize it, we must confront the reality of the market head-on and work together to create an environment that catalyzes investment for rare disease research.

See More Video Clips

By: Dr Neil Thompson, Chief Scientific Officer at Healx, a company member of the Rare Disease Company Coalition

Innovation in the biopharma industry isn’t always about the development of a new therapy for a condition – sometimes it means pioneering an entirely new approach. Right now, we’re witnessing exactly that, as artificial intelligence (AI) promises to re-engineer the entire drug discovery and development process.

Indeed, AI and other new approaches are allowing novel treatments to be designed, developed and delivered more quickly and on a scale never before seen in the industry. This is offering hope to millions of patients in need – particularly those living with a rare condition (95% of which still lack an approved treatment today).

But what are the implications of this technology for policy, patients and treatment pipelines?

How did we get here?

The historical phenotypic-based and target-based approaches of drug discovery have delivered many of the life-saving and life-changing treatments that health systems now have available to them. Yet, despite the successes, the philosophy of ‘one disease, one target, one drug’ has its limitations.

Traditionally, drugs have been developed to target a single biological entity, and it was viewed as undesirable for a drug to interact with multiple targets due to possible adverse side effects. But this approach often fails complex medical conditions, especially many rare diseases which exhibit a broad range of symptoms and causes.

Increasingly, there is evidence that a molecule hitting more than one target, or multiple molecules targeting a single disease, can create a more efficacious profile compared to single-targeted molecules. However, whilst we are seeing a slight increase in the number of multi-target therapies being approved by the FDA (21% of all FDA-approved agents between 2015-2017 were multi-target drugs), the majority of drugs being studied and in line for approval are still addressing a single target.

This poses a problem for rare diseases not only for the biological reasons mentioned above, but also because policy focused on single target therapies continues to steer therapy development towards common diseases – where there are larger patient populations from which to recoup R&D costs – meaning rare conditions remain overlooked.

Policy for progress

Advances in AI in the last decade have helped improve core processes within the drug discovery and development pipeline – from predicting protein structures and discovering new compounds, to monitoring patients during clinical trials and shaping go-to-market strategies.

AI is particularly adept at tackling the conventional challenges of rare disease treatment development. For example, Natural Language Processing (NLP) models can overcome the lack of consolidated knowledge about a rare condition by automatically scanning literature to fill in the gaps with up-to-date data. Machine Learning (ML) algorithms can speed up the drug discovery and development timeline by looking for connections between diseases and the pharmacology of compounds that are already approved for use in another condition, thereby providing valuable insight into targetable mechanisms for diseases that are still poorly understood biologically. And AI can provide the automation and scale needed to provide cost-effective treatments, thereby reducing the cost of R&D for smaller patient populations.

But therapies for rare diseases can only be developed more efficiently and cost-effectively when policy and regulation keeps up with technology. Promisingly, progress is being made in this space.

The Orphan Drug Act of 1983 ushered in a new energy to focus on rare diseases, granting financial and regulatory incentives for the biotech and pharmaceutical industry to develop treatments for them. The 21st Century Cures Act also provided additional incentives and regulatory changes, and policies like the Orphan Drug Tax Credit and the Accelerated Approval Pathway help improve the likelihood of investment in the rare disease space in order to catalyse the therapy development process and increase the likelihood of therapies reaching patients.

Then there are groups like the Rare Disease Company Coalition, who are championing further changes in policy and regulation to support technological advances in rare therapy development.

Just the beginning

What makes AI and other technological advances so fascinating is that as computing power and improvements to data quality are made, they can be rapidly scaled up. The solutions will come faster and faster as biotechs become able to automate more of the process and run more of it in parallel, with expert humans placed along the chain, at decision points where they can provide maximum impact.

It’s not hard to imagine a future where we’re able to discover treatments for whole groups of conditions at once, guided by both technological and human insight. Suddenly, no disease, however rare, need be overlooked, no question about biology left unanswered. But policies and regulations need to be in place to support these advances, so that tech-derived therapies can reach patients more quickly, especially in the rare disease sector.

Pharmacology isn’t just another discipline for AI to be applied to. It could be the most disruptive transformation in the 21st century. It is essential that government policies continue to keep pace with innovation so that novel uses of technology, including AI, can be readily deployed and utilized across treatment discovery and development to better support people with rare diseases.

We are on the cusp of great progress, we can’t afford to be slowed down now.

Bringing over 30 years experience in drug discovery and development, Neil leads Healx’s preclinical work and is deeply passionate about the application of AI to improve rare disease patient access to treatments.

Why a whole-of-society commitment makes economic sense

By: Gina Cioffi, Senior Manager of Public Affairs at Chiesi Global Rare Diseases, a company member of the Rare Disease Company Coalition. This article was written in response to a new report – “The Burden of Rare Diseases: An Economic Evaluation” – authored by experts at IQVIA and Chiesi Global Rare Diseases.

Rare diseases represent a major societal issue with enormous costs and without a clear, concentrated, whole-of-society effort to address the burden on patients, families and caregivers.

At Chiesi Global Rare Diseases, we set out to studycost drivers contributing to the burden of rare diseases to determine the societal benefit of early diagnosis and availability of pharmaceutical treatments. Along with a number of recent publications on the societal and economic burden of rare diseases, our results concur that the magnitude of the cost burden is staggering. The full report – “The Burden of Rare Diseases: An Economic Evaluation” – is available for download.

We know that lack of rare disease data compromises care and adds complexity to the innovation and drug approval process. And, the full extent of the patient, family, and societal burden will remain mostly undocumented. Our study was done through systematic review of the literature as well as expert consultation. We sought to identify new ways to better understand the cost drivers and economic impact that a lack of available treatments poses. This endeavor is critical so that policymakers can understand the benefit of investing in pharmacologic innovation, and it will encourage the development of policies to accelerate the availability of, and access to, rare disease treatments.

Discussions with patient advocacy organizations and physicians led to the selection of 24 rare diseases, each with high unmet needs, across five therapeutic areas including metabolic, neurological, congenital, hematological, and immunological. The selection criteria included the degree of unmet need, relative importance to patient advocacy organizations, interest in the scientific community, prevalence, and apparent burden of disease.

Our assessment consideredthe direct, indirect, and mortality-related costs of the selected 24 rare diseases. Direct costs include treatment, medical procedures, hospitalizations, physician visits, home healthcare, and other medical costs. Indirect costs include patient and caregiver productivity loss, work loss, home changes, and traveling and accommodation for medical visits. Mortality costs are based on value of statistical life (VSL) and the difference between average life expectancy and that for people with a rare disease.

Among our findings:

- The average overall economic burden per patient per year (PPPY) is $266,000, which is approximately 10x the cost associated with mass market diseases.

- In the detailed analysis of the selected 24 rare diseases impacting 584,000 people in the US, the total cost to society is approximately $125 billion.

- The cost burden for 8.4 million patients in the US impacted by 373 rare diseases considered in our broader analysis is estimated to be $2.2 trillion per year if treatments were available and $3.9 trillion per year if no treatments were available.

- The value returned to society if treatment were available for these 373 rare diseases is $1.7 trillion per year.

- Considering National Institutes of Health (NIH) estimates of 25–30 million Americans with a rare disease, the burden range is estimated to be $7.2 trillion to $8.6 trillion per year.

Although most direct costs are covered by government and commercial insurers, substantial indirect and out of pocket expenses impact patients and their families. We found that cost of rare diseases would be, on average, 21% more expensive PPPY if there was no access to treatment, demonstrating further that therapy access can alleviate government and family burden.

Keep in mind that these overall findings may represent an underestimation. Social costs, including the impact on health-related quality of life, were not part of this analysis.

A major strength of this study is that it presents an economic tool for analysis of the positive impact of rare disease treatments. This data can help justify increased governmental investment to ensure wider patient access to therapies and policy proposals that are reflective of the unique challenges rare disease patients and companies face.

Immediate actions that can accelerate access to treatment include passage of the Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act, providing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funding to increase its support for State Newborn Screening programs, and full funding of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Orphan Products Grant Program. Further focus to ensure legislative efforts prioritize and reflect the unique circumstances and needs of rare disease patients is another imperative.

Incentives for drug development, particularly the Orphan Drug Tax Credit (ODTC), have changed the trajectory for many rare disease patients and likely achieved significant reduction in federal spending and overall burden. Prior to the ODTC, the number of annual deaths from rare diseases was growing at a slightly higher rate than that from other diseases (2.0 percent versus 1.3 percent, respectively). In the 10 years following, the number of annual deaths from rare diseases declined at a rate of 3.1 percent, while the annual number of deaths from other diseases continued to grow at a rate of 1.2 percent. And, prior to the ODTC, only 38 drugs were FDA approved for rare diseases. Today more than 650 rare disease drugs have been approved by the agency.

Despite this success, the ODTC was targeted in the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act when Congress reduced the total amount of the tax credit for qualifying clinical testing expenses from 50 percent to 25 percent. Our industry has yet to see the full impact of that reduction, and yet in the Build Back Better Act we faced another devastating reduction to the tax credit.

Our hope is that policymakers will continue to nurture and sustain innovation based on the positive economic return from rare disease therapies.

The bottom line is that access to therapies for people living with rare diseases generates significant value for society. Now is the time for the Administration and Congress to come together with rare disease stakeholders and implement actions prioritizing the unmet needs of 30 million Americans impacted by rare diseases.

By: Dr. Jason Shafrin of FTI Consulting. This op-ed was written in response to a new white paper published by Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, a company member of the Rare Disease Company Coalition.

Although individual rare diseases have a low prevalence, one in 10 Americans is affected by one of 7,000 known rare conditions. Approximately 37 percent of rare disease patients have reduced life expectancies due to a lack of treatment options for conditions, and currently, 95 percent of rare diseases have no treatment option.[i]

Legislation, such as the Orphan Drug Act, helped increase the number of rare disease treatment options available; however, the steadily rising costs for these treatments are a cause of concern for lawmakers. As a result, policy experts are calling for a health technology assessment (HTA) framework that would determine whether the value of a pharmaceutical warrants its price.[ii]

Despite intentions to curb rising health care costs, the implementation of an HTA framework could stifle the balance of innovation in and access to orphan drugs. Research from FTI Consulting’s Center for Healthcare Economics and Policy on how orphan drugs would be affected under an HTA framework finds that the HTA framework could negatively impact innovation, development and access to orphan drugs. This is due to a tendency for many HTAs to apply a one-size-fits-all framework to orphan drugs for rare diseases, which inherently have unique needs and are high-risk endeavors.

The research finds that adopting a national HTA body based on the practices of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) could severely curtail access to orphan drugs for rare diseases.[iii] The millions of patients in the United States who already struggle to gain access to treatment for rare conditions cannot afford to lose even more access to treatment. For example, a recently approved therapy for spinal muscular atrophy underwent significant approval delays in the United Kingdom (among other countries) because the UK’s HTA body—known as NICE—determined that the price was too high to justify the treatment gains, despite robust clinical evidence that the drug showing a “substantial benefit.”[iv] Even for those on treatment, rare disease patients can benefit from improved innovations that help enable them to live longer, fulfilling lives.

Many of the value assessments conducted by current HTA bodies fail to account for broader societal benefits orphan drugs provide nor do they take into account how orphan drugs could reduce health disparities. Few HTA bodies value assessments framework incorporate value from allowing patients to return to work or school, or whether new treatment reduce the burden on parents caring for children with rare diseases. Impacts on health disparities are also largely ignored within traditional value assessment and patient advocates are concerned that negative HTA assessments will impact access. Regarding ICER’s negative assessment of new myasthenia gravis treatments, one patient advocate group stated that any barriers to care, such as ICER’s negative evaluation, “… will likely further disproportionately impact Black patients and exacerbate health inequities”.[v]

Looking ahead, applying an HTA framework to orphan drugs for rare diseases could not only hamper access to existing rare disease treatments, but also it could also decrease the likelihood that new orphan drugs will be introduced to the market. Such as the Congressional Budget Office have found that government price controls—whether due to HTA value assessment or other sources—would significantly reduce the number of new treatments that are brought to market.[vi]

As Congress is assessing current health care initiatives and programs for the future, now is an important opportunity to examine how access to rare orphan drugs are impacted through assessment under the national health technology assessment framework.

As the research points out, a one-size-fits-all model has potential negative consequences for access to and development of orphan drugs. Industry leaders, policymakers, and patient advocates can use this research as a starting point for a timely discussion on how to preserve access and innovation for orphan drugs. In order to properly address potential negative outcomes of all frameworks, a discussion is the first step. Now more than ever, it is imperative that we convene all stakeholders to build on this research. Millions of Americans living with rare diseases are depending on it.

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, Inc., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals.

FTI Consulting, Inc., including its subsidiaries and affiliates, is a consulting firm and is not a certified public accounting firm or a law firm.

_______________

[i] Stoller, James K. “The Challenge of Rare Diseases.” ScienceDirect, June 2018.

[ii] Lakdawalla, Darius et al., “Health Technology Assessment in the U.S.-A Vision for the Future.” USC Schaeffer. February 9, 2021. https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/research/health-technology-assessment-in-the-u-s-a-vision-for-the-future/

[iii] FTI Consulting, “Challenges in Preserving Access to Orphan Drugs Under an HTA Framework.” December 2, 2021.

[iv] Taylor, Phil. “Shock as NICE Turns Down Biogen’s SMA Therapy.” PMLive, August 14, 2018. http://www.pmlive.com/pharma_news/shock_as_nice_turns_down_biogens_sma_therapy_1248819.

[v] “ICER Myasthenia Gravis Public Comment.” ICER. ICER, April 2, 2021. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ICER_Myasthenia-Gravis_Public-Comment-Folio_091021.pdf.

[vi] Congressional Budget Office. CBO’s Simulation Model of New Drug Development. August 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-08/57010-New-Drug-Development.pdf

By: Aseel Bin Sawad, Pharm D, MSc, MCR, MS, PhD, DBA, Global Reimbursement and Health Economics Lead at Aeglea Biotherapeutics, a company member of the Rare Disease Company Coalition

There are 7,000 to 10,000 rare diseases when looking at all rare diseases in a collective manner.1 Around 25 to 30 million Americans suffer from rare diseases which equates to 1 in every 10 individuals and 50% are children.2-4

Many rare diseases are life-threatening and progressive with substantial morbidity and early mortality.5,6 Unfortunately, only 5 to 7% of rare diseases have FDA-approved treatments, and the majority of these treatments (75%) treat only one rare disease.7

It is imperative to understand the unique challenges of the entire rare disease ecosystem to provide cost-effective and timely access to treatments for people living with rare diseases.

The Challenges

Challenges associated with rare diseases include, but are not limited to, the ability to make an accurate and timely diagnosis; overwhelming clinical burden; lack of adequate real-world data; ability to quantify the economic burden; and pricing and access.

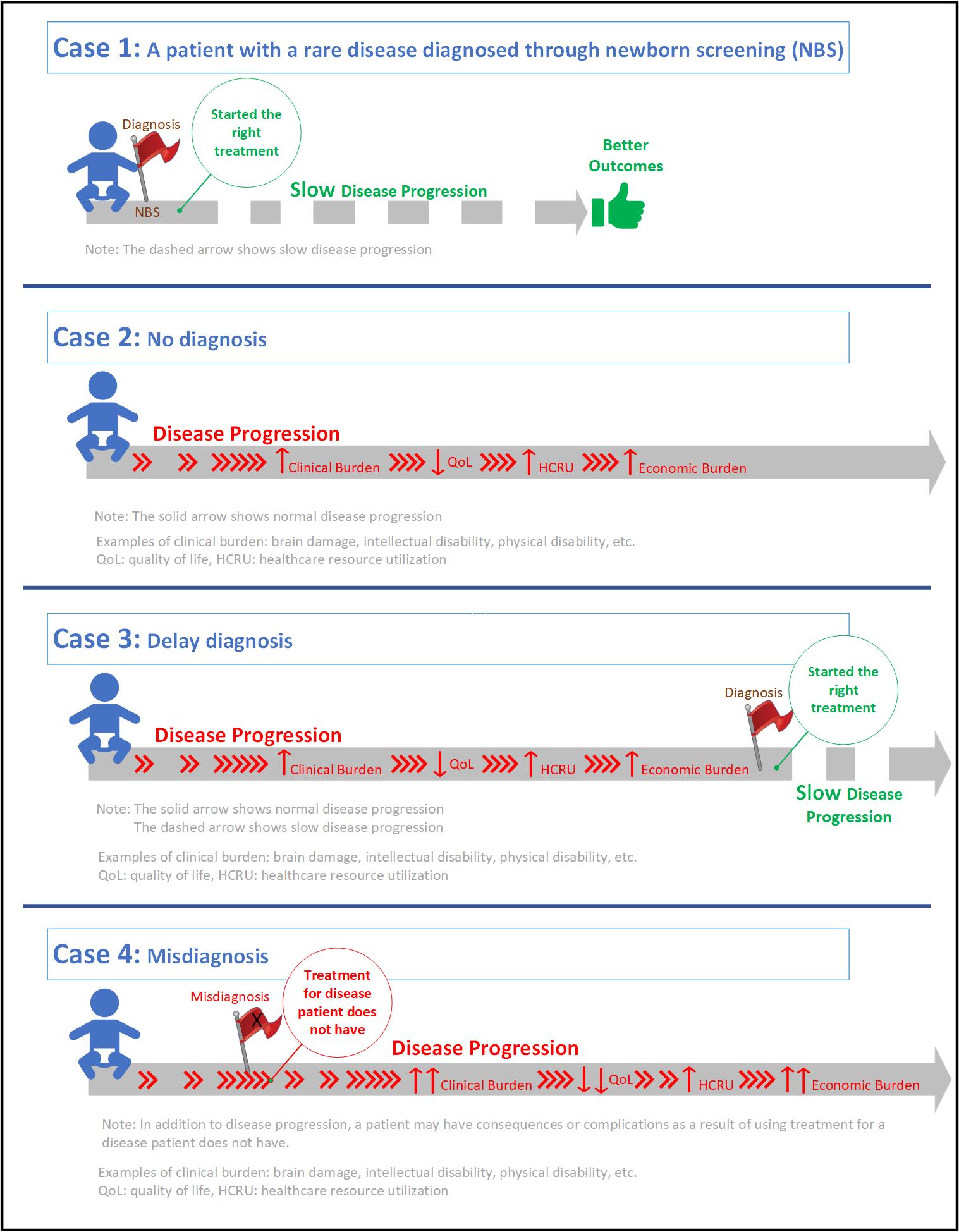

Diagnoses that are Delayed, Undiagnosed and/or Misdiagnosed

It is common for rare diseases to go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed for years, leading to serious complications such as brain damage, intellectual disability, physical disability, among others. Many rare diseases are associated with a poor quality of life due to their progressive nature, extensive utilization of healthcare resources to manage symptoms, and a substantial economic burden on the patients, caregivers and healthcare system.5,6 A recent study shows that diagnostic journeys of patients with rare diseases are lengthy and delay in diagnosis results in advanced, irreversible, and costly complications.8 Despite being born with the condition (i.e., genetic rare disease), one study reports that patients were not accurately diagnosed until an average age of 6.4 years.9

Inherited metabolic disorders are good examples of the unique challenges posed by rare diseases. While affected infants can be diagnosed through newborn screening (NBS), there are limitations. NBS is not available for most rare diseases, and for those that are included in NBS, the availability and reliability may vary from state to state. In some cases, there is lack of consistency in using appropriate analytical cut-off values for disease indicators.10,11 In addition, false negative results can occur because some plasma enzymes may take time to accumulate in newborns.12

Another challenge during the diagnosis of rare diseases is the heterogeneity of the symptoms. You can find two siblings having the same rare disease, but they have different symptoms. Similarly, many rare diseases often share similar symptomatology, leading to a misdiagnosis. Due to the extremely low prevalence of certain rare diseases, even the ‘disease experts’ may only see a handful of cases in their entire career.

Misdiagnosis can also result in a delayed diagnosis, but with extra clinical and economic burden. Patients may experience serious clinical adverse events due to medications prescribed for a disease that they do not have. In addition, further utilization of healthcare resources such as physician visits, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations, leads to extra economic burden (on the patients, caregivers and healthcare system) while patients continue the progression of their underlying, actual disease.

These examples visualize the differences between a patient who was diagnosed with a rare disease at the right time (Case 1), a patient who was not diagnosed (Case 2), a patient whose diagnosis was delayed (Case 3), and a patient who was misdiagnosed (Case 4).

We call on policymakers to make informed decisions when it comes to rare diseases, to support and expand early diagnosis programs like NBS and timely patient access to orphan drugs to enable better health outcomes.

Congress must also preserve and increase incentives to continue attracting, encouraging, and enhancing long-term investments and innovations of rare disease diagnostics and treatments. It is less expensive for the healthcare system to diagnose a patient on time versus risking complications or a massive event where a child, or others, ends up needing long-term care through state aid.

As we move into 2022, we must look at the big picture to ensure that rare disease patients live the quality of life they deserve, and receive the right diagnosis, at the right time, with the right support.

References

- Haendel M, Vasilevsky N, Unni D, Bologa C, Harris N, Rehm H, Hamosh A, Baynam G, Groza T, McMurry J, Dawkins J, Rath A, Thaxon C, Bocci G, Joachimiak MP, Kohler S, Robinson PN, Mungall C, Oprea RI. How many rare diseases are there? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(2):77–8. https://doi. org/10.1038/d41573-019-00180-y.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Chapter 2. Profle of rare diseases. IOM (US) committee on accelerating rare diseases research and orphan product development. In: Field MJ, Boat TF (eds). National Academies Press (US), Washington, DC; 2010. https://doi.org/10.17226/12953.

- NCOD (National Commission on Orphan Diseases). Report of the national commission on orphan diseases. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD; 1989.

- NIH NCATS. Genetics and rare diseases information center. FAQs about rare diseases. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/pages/31/faqs- about-rare-diseases. Accessed 06 November 2021.

- Klimova B, Storek M, Valis M, Kuca K. Global view on rare diseases: a mini review. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24:3153–8. https://doi.org/10.2174/09298 67324666170511111803.

- Ryder S, Leadley RM, Armstrong N, Westwood M, de Kock S, Butt T, Jain M, Kleijnen J. The burden, epidemiology, costs and treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an evidence review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-017-0631-3.

- NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). A NORD® Commissioned Report with Avalere®. Orphan drugs in the United States: An examination of patents and orphan drug exclusivity. 2021. https://rarediseases.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NORD-Avalere-Report-2021_FNL-1.pdf. Accessed 07 November 2021.

- Tisdale A, Cutillo CM, Nathan R, Russo P, Laraway B, Haendel M, Nowak D, Hasche C, Chan CH, Griese E, Dawkins H. The IDeaS initiative: Pilot study to assess the impact of rare diseases on patients and healthcare systems. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):1–8. https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s13023-021-02061-3.pdf

- Bin Sawad A, Pothukuchy A, Badeaux M, Hodson V, Bubb G, Lindsley K, Uyei J, Diaz GA. The natural history, clinical outcomes and unmet needs of patients with Arginase 1 Deficiency (ARG1-D): A systematic review of case reports. Value in Health. 2021 Jun 1;24:S4.

- Cederbaum S, Therrell B, Currier R, Lapidus D, Grimm M. Newborn screening for arginase deficiency in the U.S. – Where do we need to go? Paper presented at: ACMG Annual Clinical Genetics Meeting2017.

- Therrell BL, Currier R, Lapidus D, Grimm M, Cederbaum SD. Newborn screening for hyperargininemia due to arginase 1 deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;121(4):308-313.

- Jay A, Seeterlin M, Stanley E, Grier R. Case Report of Argininemia: The Utility of the Arginine/Ornithine Ratio for Newborn Screening (NBS). JIMD Rep. 2013;9:121-124.

By: Betsy Ricketts, Chair of the Rare Disease Company Coalition, and Vice President of Policy, Government and Public Affairs at Ultragenyx, a company member of the Rare Disease Company Coalition

Originally Published at TheHill.com (December 29, 2021)

Congress’s proposed limits to the Orphan Drug Tax Credit (ODTC) in the Build Back Better Act (H.R. 5376) could severely hurt development of potential treatments for rare diseases that impact 30 million people in the United States, half of whom are children. It is difficult to understand how Congress could agree to the drastic reduction of this proven resource that supports the development of new treatments for 90 percent of the approximately 7,000 known rare diseases that currently do not have an FDA-approved treatment, many of which are life-limiting or fatal.

To understand the significance of the ODTC, it is important to understand the unique challenges — and promises — in taking rare disease drugs from research through development, approval, manufacturing and delivery to patients. Rare diseases have small patient populations, which makes developing drugs to treat them inherently more difficult, costly, and risky than those for common medical conditions. The ODTC incentivizes biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies to invest in the development of treatments that are not otherwise economically viable.

In 1983, recognizing rare diseases historically have attracted minimal attention, Congress established the Orphan Drug Act (ODA), creating the tax credit for advancement of rare disease treatments. At the time, only 38 drugs had been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for rare diseases. Now, thanks to this effective and long-standing public health policy, there are more than 650 drugs approved to treat rare diseases. Most importantly, this has led to a significant and consistent decline in the number of annual deaths from rare diseases.

Congress should not be focused on snatching hope from those living with rare diseases; our representatives should instead support and enhance existing rare disease policy because it is working. Of note, the FDA affirmed the value of the ODA and this incentive in an Office of Inspector General (OIG) report issued in September. Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.) also recently called for the complete restoration of the ODTC after it was reduced from 50 to 25 percent in 2017.

Continue Reading at The Hill.com

By: Leslie Meltzer, Ph.D., Chief Medical Officer at Orchard Therapeutics, a company member of the Rare Disease Company Coalition

In the first 24 to 48 hours of a baby’s life, a small blood sample is taken to detect serious genetic conditions, some of them deadly, that can be treated if diagnosed early. Thanks to newborn screening (NBS), a critical public health program that screens about 4 million babies a year in the U.S., parents have the opportunity for timely diagnosis, medical guidance, and disease intervention for their babies.

This NBS Awareness Month, advocates in the field, while praising the system for its many accomplishments and lives saved, are also raising red flags about its capacity to handle the coming wave of innovative gene and cell therapies approaching regulatory approval in the U.S. These therapies can bring hope to families facing rare genetic conditions, but for many of these disorders diagnosis as early as possible is often critical to successful intervention – making newborn screening crucial.

The NBS system needs modernization.

In the last 15 years, only six conditions were added to the Federal Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP). On average, it takes approximately six years from the time a condition is nominated until it is added to the RUSP, if it is included at all. Even if added to the RUSP, screening in all 50 states can take up to a decade. For example, SCID was added to the RUSP in 2010; however, the condition was included on the first state panel in 2008 but was not added to all state panels until 2018. That means a baby born in one state can have the advantage of diagnosis, medical guidance, and treatment for an addressable genetic condition, while a baby born over the state line may face disability or early death for lack of testing.

More than 60 new gene therapy treatments – many for serious and rare conditions in children – are expected by 2030. This is therefore the right moment to look carefully at NBS capacities and screening implementation timelines with an eye on what is coming in terms of new therapies. An innovation in rare disease therapy almost always requires timely diagnosis and medical guidance in order for patients to benefit from therapy.

Continue reading here.

By: Habib Dable, CEO of Acceleron Pharma, a company member of the Rare Disease Company Coalition

Originally published on MassBio.org (July 20, 2021)

In the biopharmaceutical industry, this refrain is as familiar as it is true. For those of us at companies committed to developing potentially transformative medicines to treat any of the approximately 7,000 recognized rare diseases—93% of which have no FDA-approved treatment—this call to action has never felt more attainable, yet at the same time, more at risk.

As legislators contemplate a range of access and pricing reforms in this era of rising costs and constrained resources, there is a considerable temptation among legislators to paint our industry with a single broad brush. Such one-size-fits-all policy approaches are a very real threat to the innovation that fuels the hopes of the small but needful patient populations we endeavor to serve. Further, such policies fail to recognize or reward the level of risk that smaller, rare-disease-focused companies—historically, the companies best suited to producing true advances in their chosen spaces—incur through much of their existence.

Before becoming CEO of Acceleron, I spent more than 20 years in classic “big pharma” at a multinational corporation with a vast portfolio of marketed drugs to treat prevalent diseases across a breadth of therapeutic areas. Revenues supported nearly 100,000 employees worldwide and funded a robust research pipeline. This is most certainly not the business model my rare disease counterparts and I execute on. Many of us are in the pre-clinical, clinical or early commercial stage, relying almost entirely on investors for funding as we seek meaningful therapeutic advances. Many of us may only have one or two seemingly viable assets, a precarious state in an industry in which failure is far more often the rule rather than the exception.

Continue reading at MassBio.org

By: Emil D. Kakkis is the CEO, president, and founder of Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical, a company member of the Rare Disease Company Coalition

The FDA’s decision to grant accelerated approval to Biogen’s aducanumab (Aduhelm) for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease was a difficult and bold one that people with the disease, their families, and other drug developers should be applauding.

When it comes to making new therapies for complex, difficult-to-treat diseases, history has shown that progress can’t be made without taking a first — often controversial — step. Without the FDA’s accelerated approval program and novel first treatments based on new and imperfect biomarker endpoints, HIV would not be a controllable disease today, and we might not have such a flourishing clinical research ecosystem in oncology.

Continue reading at STAT News.